In the grand tradition of prose poems, Marcus Silcock’s delightful Dream Dust is surreal, for sure, but in a way that complements rather than covers up the truth. Personal recollections and strong narrative undertones lie just below the bright, windy surface. These charming fictions take place all over the world but their subject is always what it looks like to be fully human, to be fully present, wherever you happen to be. Dream Dust makes a fine traveling companion.

Matthew Rohrer

Marcus Silcock’s newest collection, Dream Dust, is a masterful assemblage of prose poems. Are they autobiographical surrealisms or surrealist autobiographies? You decide. From Vegas to Seoul to Sitges to Wrocław, here we have a cosmic trip disguised as an international voyage. Prose poems with heart and dilated pupils. Tender yet absurd. Hallucinatory and strange, twirling through a fable, like taking psychedelics in the American desert and waking up in a Polish forest. Instead of a spaghetti western, this is a pierogi fever dream. This unique collection is full of forests and beer steins and cultural ceremonies and Eastern European architecture and magic broth. It’s global, musical, and nostalgic every step of the way, like finding a tattered diary in a bowl of borscht. “You can count the tree rings on my forehead,” Silcock promises us, later stating, “I am surrendering to this experience.” We believe him and so we do the same. Through it all, Dream Dust is packed with sharp, punchy memories. Scraps of the past splashed in a foggy dew. If you try to find your way through these riveting narratives, know the compass is spinning and the map has caught fire. To open this book is to “roll the bone dice” and begin a new game. Give it a shot. See where you land.

Ben Niespodziany

Dream Dust is an encyclopaedia of peculiarities and particularities. The title piece begins: ‘This place is famous for shits and giggles.’ These prose poems or micro-narratives are typically laconic; not infrequently metaphysical and/or philosophical. ‘How uninteresting interesting things can become,’ said Robert Walser’, the German Swiss poet known as ‘the poet of miniatures’. Dream Dust is supple and ludic and deadpan and serious and invigorating and comic. In quasi-Swiftian mode we find ourselves stumbling upon ‘Giant metal babies crawling with their metal bums in the air.’ Seemingly, ‘[t]hose metallic bums were the future.’ The book signs off with ‘Hungry Ghosts’. The speaker follows ‘the white monkey (Biała Małpa) down the hole and into the beer garden.’ A little later ‘Someone smiles. Miles & miles of good smile.’

Julian Stannard

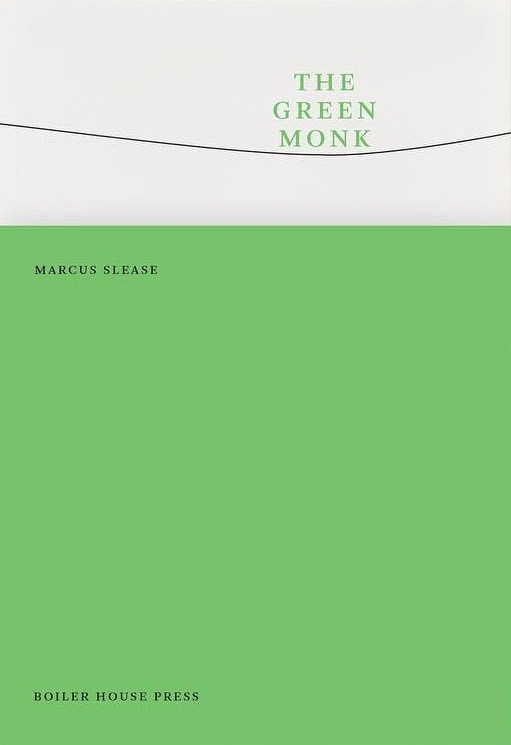

The Green Monk is a fantastic book, the work of a writer with great technical artistry, but a writer who deploys that artistry with subtly and restraint. These pieces are dreamscapes, creating and residing within their own bubbles of wonderland white logic. They have the strangeness of translations, although they are not translations. The Green Monk is an umbrella meeting a sewing machine uptown. Poetry needs line breaks like a fish needs a fish tank.

Tom Jenks

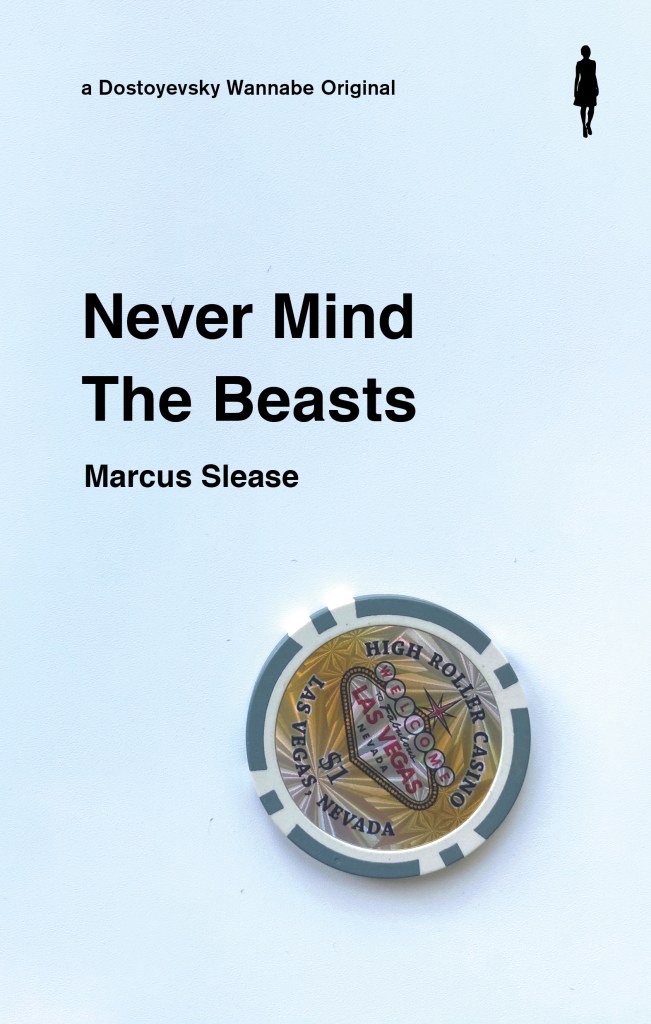

Say Lydia Davis and Donald Barthelme had a son, and his life story was painted by Basquiat, and the paintings were ground up into a spice, then used to flavour a crazy-hot dish you just can’t stop eating while the scenery shifts around you: that taste might be something like Never Mind the Beasts.

Ruby Cowling

Writing actually as love! Marcus Slease’s crinkling, crackling prose is full of sparks, full of troubles, full of wonder. Never Mind the Beasts radiates with the force, brevity and immediacy of stylists like Mary Robison, Rikki Ducornet and Diane Williams. “The demand to love,” wrote Roland Barthes at the beginning of Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes; “overflows, leaks, skids, shifts, slips.” “Writing to touch with letters, with lips, with breath,” wrote Hélène Cixous in Coming to Writing. These are the thrilling, vibratory spaces, movements and possibilities Slease’s writing opens up.

Colin Herd

(co-editor and contributor)

‘Spectacularly subversive and darkly potent, The Surreal-Absurd Anthology is an extraordinary manifesto for contemporary surreal-absurdism. In this collection, the editors bring together the finest poets working in the field to create the definitive work on this emerging form, celebrating the growing and uncanny relevance of this “open-ended movement”.’ – Cassandra Atherton

‘It often feels like I’m the only weirdo at the party. But these authors remind me that while everyone is pretending to be balanced and rational, inside we are plagued by, and delighted by, our weirdness and idiosyncrasy. I get excited every time I sit down with one of these authors, and I’m incredibly proud to be featured alongside them.’ – Kiik Araki-Kawaguchi

‘A comprehensive and brilliantly edited anthology of the Surreal-Absurd: easily my favourite since Edward B. Germain’s English and American Surrealist Poetry, published by Penguin back in 1978.’ – Ian Seed